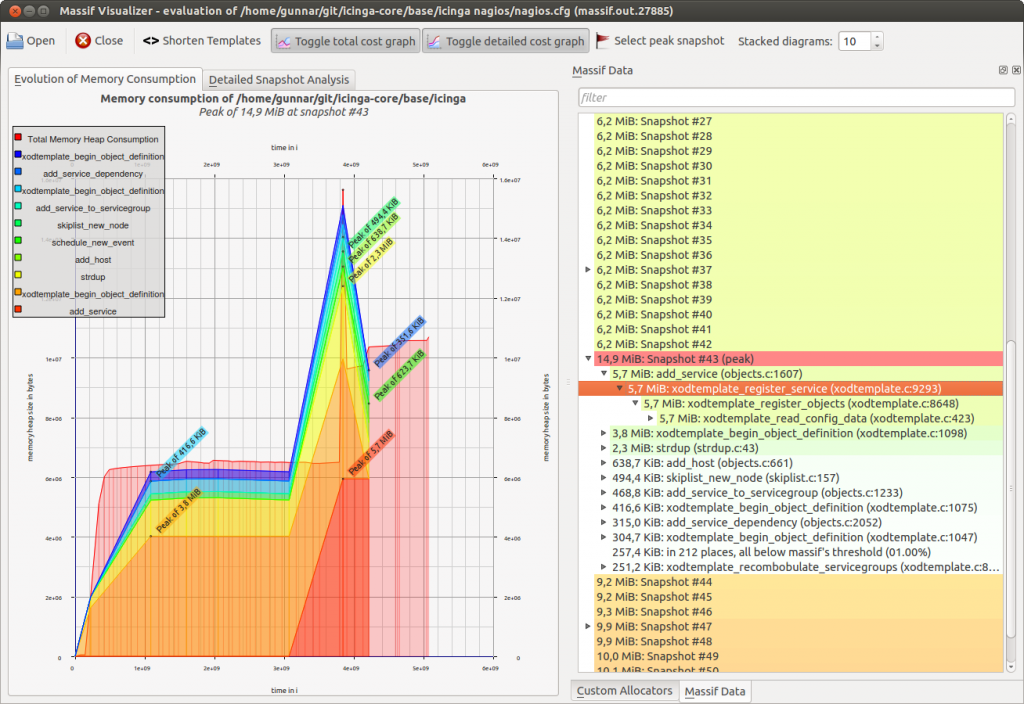

We are using a variety of tools to ensure that our applications do not leak memory, suffer from performance issues or actually trigger unwanted behavior. This tool stack changes over time, and it is also different for web, script and binary applications. Next to the Icinga bits I am responsible for the LConf Backend and other Perl foo here at NETWAYS – I’ve already written about profiling Perl. During Icinga 1.x and 2.x development we’ve come around a couple of tools for profiling memory consumption with Massif or using the Google perftools.

One of our specialties at NETWAYS Development is further that we’re capable of identifying and resolving issues directly – be it performance, memory, locking, race conditions, etc. aside from the code we’re developing and running at customers.

The perfect code vs performance

While the perfect code does not exist, it’s always interesting and also required to refactor your own code parts based on current conditions and requirements. The code in 2.2.4 had one function interface being called, namely AddObject(). This function is merely doing the following for ‚repository add‘ and ’node update-config‘:

- Get all the object names from `repository.d` and checking if the added object already exists

- Create a new object by attributes and run it against the Icinga 2’s config validation

- Check if the change already exists by reading the `changes` directory

- Add the change to the changelog (for calling ‚commit‘ later on)

This is perfectly fine for keeping the same functionality shared among several occasions where this code is used. But we’ve run into severe performance issues with like 20000 calls to AddObject() inside one ’node update-config‘ run.

How to tackle the problem

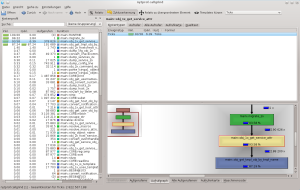

Valgrind provides a tool named callgrind which tracks the function calls and time of a specific binary being run. While this is a bit slower than the Google perftools, it provides more detailed data. The ‚callgring.out.PID‘ file can then be visualized in KCacheGrind.

Install Valgrind alongside with KcacheGrind. I’m using Fedora 21, other distributions use similar package names.

# yum install valgrind kcachegrind graphviz

In order to profile Icinga 2 with all debug symbols included, I’m compiling Icinga 2 with debug symbols enabled: -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug (Note: Using Icinga 2 packages you’ll get a separate package).

Valgrind requires a bunch of parameters which are easier being modified in a small script. I’m also running the direct debug build binaries instead of the installed binary here. Generating some sort of huge debug config inside the Icinga 2 cluster and node inventory is left to the reader’s imagination 😉 (I’ll write a different blog post for that sooner or later).

# vim callgrind_icinga2 #!/bin/bash valgrind \ -v \ --trace-children=yes \ --tool=callgrind \ --simulate-cache=yes \ --collect-jumps=yes \ --dump-instr=yes \ --dump-line=yes \ /home/michi/coding/icinga/icinga2/debug/Bin/Debug/icinga2 node update-config # sudo ./callgrind_icinga2

If you want to enforce a manual dump before the program ends, you can invoke the following command:

# callgrind_control -d

Visualize and analyze the bottlenecks

Opening the callgrind.out file(s)

$ sudo kcachegrind callgrind.out.16903

unveiled that there were certain unnecessary calls to generic functions.

- Getting objects/changes on each AddObject() call is useless

- ’node update-config‘ would cause AddObject() to validate each object. But we know already we’re right not parsing user’s input from the cli arguments.

Solve the problem

Refactoring the code and allowing to pass one-time collected objects/changes as well as suppressing configuration validation solved the problem in the end. Still it unveiled that you should sometimes stop feature development and profile your own application 🙂